When a Woman Ascends the Stairs

When a Woman Ascends the StairsA film by Mikio Naruse

Country : Japan

Year : 1960

Japanese with English sub titles

24th April 2011

Perks Mini Theater

* 13 minutes interview with actor Tatsuya Nakadai

will be shown with the main film.

Mikio Naruse creates an exquisitely realized, somber, and deeply affecting portrait of dignity and perseverance in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs. Using the recurring image of Keiko ascending the stairs that lead to the bar, Naruse reflects Keiko's symbolic transcendence from her increasingly disreputable profession. The dilemma is that she is approaching an age when her looks might be expected to fade, and so she is encouraged either to start her own bar or to get married. Either path seems to involve a sacrifice of independence

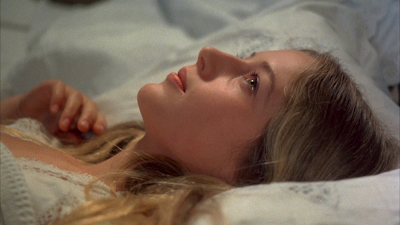

Mikio Naruse creates an exquisitely realized, somber, and deeply affecting portrait of dignity and perseverance in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs. Using the recurring image of Keiko ascending the stairs that lead to the bar, Naruse reflects Keiko's symbolic transcendence from her increasingly disreputable profession. The dilemma is that she is approaching an age when her looks might be expected to fade, and so she is encouraged either to start her own bar or to get married. Either path seems to involve a sacrifice of independence At the film’s center is Hideko Takamine, one of Naruse’s favorite actresses and indeed one of the most striking, gifted, and charismatic stars in Japanese cinema. She plays Keiko, a widow who supports herself as a bar madam, the chief attraction in whatever bar she works, by virtue of her beauty and superior refinement.

At the film’s center is Hideko Takamine, one of Naruse’s favorite actresses and indeed one of the most striking, gifted, and charismatic stars in Japanese cinema. She plays Keiko, a widow who supports herself as a bar madam, the chief attraction in whatever bar she works, by virtue of her beauty and superior refinement.  Every afternoon, Keiko (Hideko Takamine) walks from her modest apartment to her job as a senior hostess in a Ginza bar. Compassionate and courteous, she is affectionately called "mama" by the younger hostesses who see her graciousness and charm as an unattainable ideal..

Every afternoon, Keiko (Hideko Takamine) walks from her modest apartment to her job as a senior hostess in a Ginza bar. Compassionate and courteous, she is affectionately called "mama" by the younger hostesses who see her graciousness and charm as an unattainable ideal.. Naruse’s filming style, never ostentatious, shows exquisite tact. Like Roberto Rossellini, another filmmaker of unfailing intelligence, Naruse directs facts; he constructs the image only enough to get its essential meaning across. There are no bravura 360-degree camera movements, but there are subtle little tracking shots of Keiko walking through Tokyo, with or without company; and when Keiko goes up the stairs to her bar, the camera delicately ascends with her for just two seconds.

Naruse’s filming style, never ostentatious, shows exquisite tact. Like Roberto Rossellini, another filmmaker of unfailing intelligence, Naruse directs facts; he constructs the image only enough to get its essential meaning across. There are no bravura 360-degree camera movements, but there are subtle little tracking shots of Keiko walking through Tokyo, with or without company; and when Keiko goes up the stairs to her bar, the camera delicately ascends with her for just two seconds. Though we cannot but sympathize with Keiko, we are also allowed to judge her dispassionately. She comes across at times as self-righteous, at other times as hard. It is a strength of character that is reflected in her early narrative: "After it gets dark, I have to climb the stairs, and that's what I hate. But once I'm up, I can take whatever happens." Inevitably, the daunting stairs provide a reassuring ritual from crushing disillusionment and personal tragedy - a validation of courage and resilience in facing the unknown - a quiet triumph of the human spirit.

Though we cannot but sympathize with Keiko, we are also allowed to judge her dispassionately. She comes across at times as self-righteous, at other times as hard. It is a strength of character that is reflected in her early narrative: "After it gets dark, I have to climb the stairs, and that's what I hate. But once I'm up, I can take whatever happens." Inevitably, the daunting stairs provide a reassuring ritual from crushing disillusionment and personal tragedy - a validation of courage and resilience in facing the unknown - a quiet triumph of the human spirit.(Source:Internet)

Mikio Naruse, often ranked with Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu as one of the three master Japanese directors who were at their peak in both the prewar and postwar eras, was born in Tokyo on August 20, 1905. The son of an impoverished embroiderer, Naruse developed a love of literature from an early age. Because of his family’s financial problems, he was unable to continue his education into middle school, attending instead a technical school. Naruse’s father died when he was 15, forcing him to take a job to support the family. Through a friend, he began working as a prop man at the Shochiku film company in Tokyo in 1920. Naruse finally had an opportunity to direct, making his debut with a slapstick comedy, Chambara Fufu . Naruse demonstrated a lyrical style in his second film, Junjo (Pure Love) (1930), a work which won the praise of another Shochiku director, Yasujiro Ozu.

In 1933, Naruse reached his pinnacle in the silent cinema with two masterpieces crystallizing themes that would dominate his work for the rest of his career. In 1937, Naruse married Sachiko Chiba, who had played the heroine of Tsuma yo Bara no yo Ni. The two had a child, although they later divorced, and Naruse resumed his bachelor way of life, residing in a modest apartment and frequenting bars, until his second marriage in later years. Naruse continued to make films throughout the war years. The director recovered from an apparent postwar slump of lesser films with his 1951 drama, Ginza Gesho (Ginza Cosmetics), starring Kinuyo Tanaka.

Naruse that he went on to direct for Toho a series of films in the 1950s and 1960s that rank as the masterpieces of his maturity. Six of these films were adapted from stories by Fumiko Hayashi, a woman writer who had dramatized her own struggles in fiction and whose point of view held enormous appeal for the director.Other classic films Naruse directed in the postwar years include Okasan (Mother) in 1952, Yama no Oto (Sound of the Mountain) in 1954, Nagareru (Flowing) in 1956, and Onna ga Kaidan o Agaru Toki (When a Woman Ascends the Stairs) in 1960.

Naruse continued to direct for most of the 1960s, his final film being Midaregumo (Scattered Clouds), He died on July 2, 1969, at the age of 63. In 37 years of directing, he had made a phenomenal 87 films. Through all those decades, he had maintained a consistent personal vision in most of his work. However, he had modified his cinematic approach since his earliest films. Whereas in many of his silents, he had experimented with a wide variety of techniques, in his talkies, he opted for a more subdued visual style. He now limited camera movement and avoided unusual camera angles and rapid montage in order to place full emphasis on the facial expressions and gestures of the actor. In the years since his death, Naruse’s reputation has continued to grow with retrospectives of his work, and many now recognize him as one of the supreme masters of world cinema.

(Source: Internet)

In 1933, Naruse reached his pinnacle in the silent cinema with two masterpieces crystallizing themes that would dominate his work for the rest of his career. In 1937, Naruse married Sachiko Chiba, who had played the heroine of Tsuma yo Bara no yo Ni. The two had a child, although they later divorced, and Naruse resumed his bachelor way of life, residing in a modest apartment and frequenting bars, until his second marriage in later years. Naruse continued to make films throughout the war years. The director recovered from an apparent postwar slump of lesser films with his 1951 drama, Ginza Gesho (Ginza Cosmetics), starring Kinuyo Tanaka.

Naruse that he went on to direct for Toho a series of films in the 1950s and 1960s that rank as the masterpieces of his maturity. Six of these films were adapted from stories by Fumiko Hayashi, a woman writer who had dramatized her own struggles in fiction and whose point of view held enormous appeal for the director.Other classic films Naruse directed in the postwar years include Okasan (Mother) in 1952, Yama no Oto (Sound of the Mountain) in 1954, Nagareru (Flowing) in 1956, and Onna ga Kaidan o Agaru Toki (When a Woman Ascends the Stairs) in 1960.

Naruse continued to direct for most of the 1960s, his final film being Midaregumo (Scattered Clouds), He died on July 2, 1969, at the age of 63. In 37 years of directing, he had made a phenomenal 87 films. Through all those decades, he had maintained a consistent personal vision in most of his work. However, he had modified his cinematic approach since his earliest films. Whereas in many of his silents, he had experimented with a wide variety of techniques, in his talkies, he opted for a more subdued visual style. He now limited camera movement and avoided unusual camera angles and rapid montage in order to place full emphasis on the facial expressions and gestures of the actor. In the years since his death, Naruse’s reputation has continued to grow with retrospectives of his work, and many now recognize him as one of the supreme masters of world cinema.

(Source: Internet)